May 28, 2019

Klamath's Bone-Dry Wetland

(Originally printed in the Summer 2019 issue of California Waterfowl Magazine.)

by JEFFREY A. VOLBERG, DIRECTOR OF WATER LAW AND POLICY

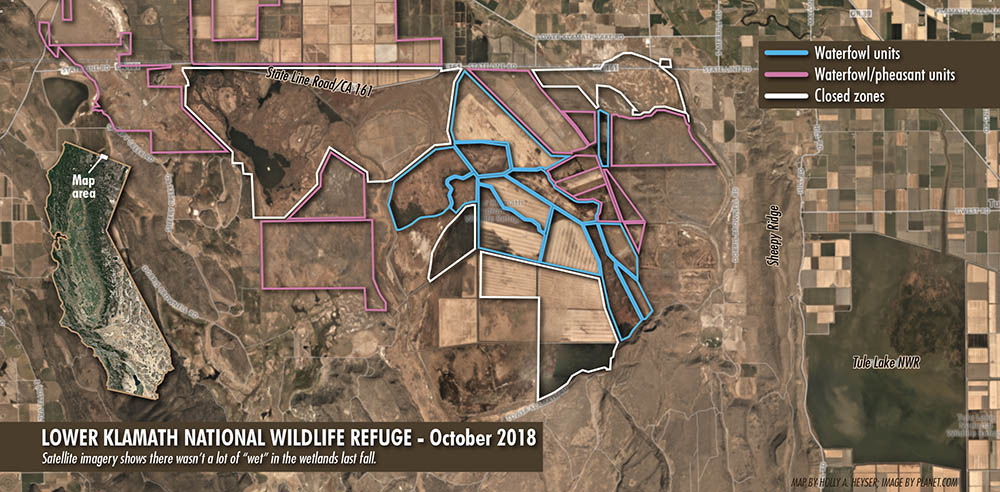

Driving down the highway that straddles the California-Oregon border on opening day of duck season last fall, hunters were horrified to find the marsh bone dry on both sides of Route 161, something veteran waterfowlers there had never seen. A survey found only 29,000 ducks and 120,000 geese using the limited water on the refuge, where usually there would have been 450,000 ducks and even more geese.

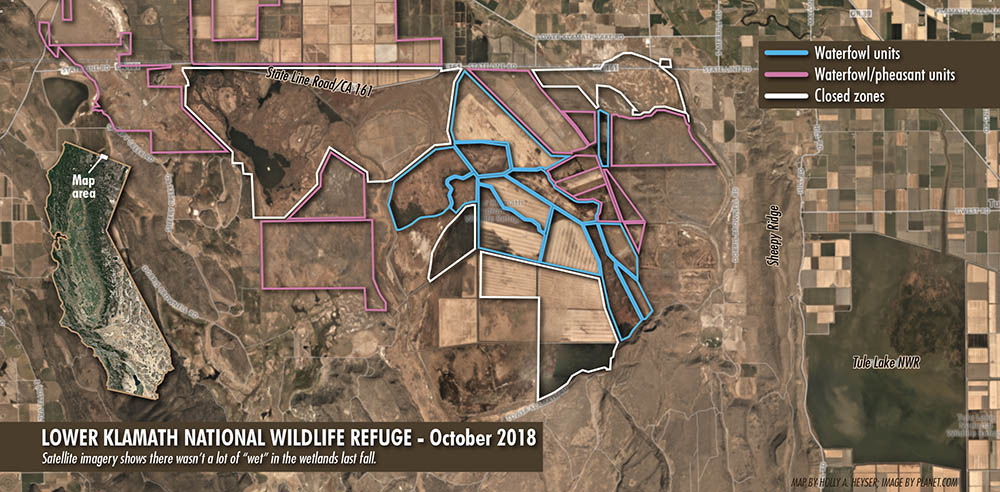

That summer, water deliveries to the refuge stopped because of two lawsuits seeking more water for endangered fish species. Mallards and other locally breeding ducks had already established nests before the water went away, stranding flightless ducklings. We don’t know how many broods were lost, but we do know that 22% fewer mallards were harvested at state-run refuges last season, despite a 38% increase in the state’s breeding population in 2018.

The lack of water was due to both natural and man-made causes that began long before last year. It’s a complex problem with no simple or obvious solutions, but California Waterfowl has been working hard to ensure it is not the new normal.

CRITICAL FOR MORE THAN JUST NORTHEASTERN HUNTERS

Besides being the oldest waterfowl refuge in the United States, the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge has some unique characteristics. When properly supplied with water, the refuge supports waterfowl throughout their life cycles.

Most hunters probably think of this huge refuge in the Northeastern Zone as one of the first places we can hunt ducks in California each hunting season. But it actually plays a much bigger role for all waterfowl in the Pacific Flyway, so its condition affects the birds everyone hunts in the rest of the state all winter long.

Its most important function is as a spring staging ground where waterfowl— including pintail—can bulk up for the trip north to breed. Some ducks stay behind and breed there—in fact, about 40% of all breeding mallards in California were in the Northeastern Zone during last year’s population survey, and Lower Klamath is a significant part of Northeastern’s breeding habitat. Mallards’ reliance on this region is growing as breeding habitat declines in the Central Valley.

Its most important function is as a spring staging ground where waterfowl— including pintail—can bulk up for the trip north to breed. Some ducks stay behind and breed there—in fact, about 40% of all breeding mallards in California were in the Northeastern Zone during last year’s population survey, and Lower Klamath is a significant part of Northeastern’s breeding habitat. Mallards’ reliance on this region is growing as breeding habitat declines in the Central Valley.

In late summer, it provides critical refuge to molting ducks, which lose all of their flight feathers during molt and need vast areas where they can stay safe from predators—something that’s in extremely short supply in the Central Valley. More than half of California’s mallards molt in the Klamath Basin, and when Lower Klamath runs dry, it concentrates more birds at the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge, which can exacerbate botulism outbreaks that occur there naturally each summer, causing massive die-offs.

It’s also a key refuge for shorebirds, sandhill cranes and bald eagles, driving substantial bird-watching tourism that benefits the region.

WHERE THE WATER USED TO COME FROM

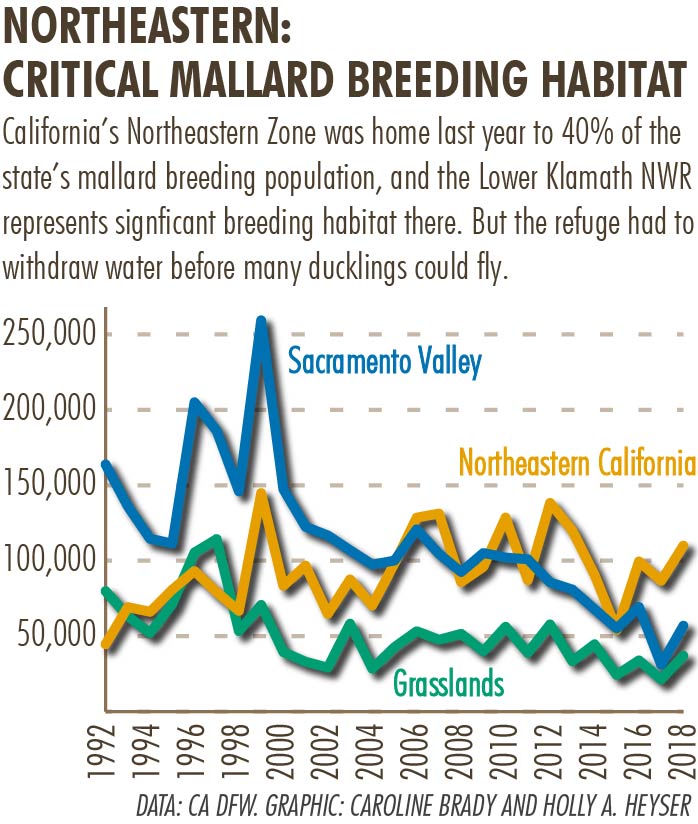

The Lower Klamath refuge sits partly in California and partly in Oregon. Its water rights, however, are Oregon water rights from the Klamath River and its tributaries. When the Bureau of Reclamation built the Klamath Project for farm irrigation, the Lower Klamath was not designated a purpose of the Project. Nevertheless, the Klamath Project provided water to the refuge every year directly through the Ady Canal, the main artery for water supplied from the Klamath River.

It also provided water indirectly from the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Tule Lake collects runoff water from the Klamath Project in large sumps. To prevent flooding of the Tule Lake farmlands, the excess water is pumped through a tunnel under Sheepy Ridge to the Lower Klamath refuge. This supply is mainly available in the fall and winter. The Ady Canal provided water in other seasons, as well.

All told, the refuge used to receive up to 130,000 acre feet of water, with an average of over 100,000 acre feet.

Until 2006, the Tulelake Irrigation District had a very favorable power contract with the local utility, which made pumping through the hill affordable. The power contract expired in 2006 and the price of electricity increased dramatically, making the cost of pumping prohibitive. The district still has to pump a small amount to avoid flooding, but the average amount of water pumped has dropped by more than half because the irrigation district cannot afford the increased cost.

WHAT DO FISH HAVE TO DO WITH THIS?

The listing of coho salmon, Lost River suckers, and shortnose suckers as endangered species in the 1990s has affected the way water can be used in the Klamath Basin. Under the Endangered Species Act, the endangered species have first priority for water, then the irrigators, and finally the refuge. If there is not enough water to go around, the refuge is first to be cut off. This does not make much sense because the entire Klamath Basin was a huge wetland until 1906.

In 2001, farmers were cut off too when the Klamath Project closed its headgates and canals. The farmers and federal employees reached an armed standoff when the farmers tried to open the headgates and put water in the canals. Since then, there has been a tension between providing water to avoid extinction of the endangered species and the needs of other water users in the Klamath Basin.

Ironically, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is responsible for protecting the endangered fish species and also operates the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, including the Lower Klamath refuge. The Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service are both agencies under the U.S. Department of Interior and its secretary. Yet, it seems in many years, the Bureau and the Service are working against each other, and the fisheries wing of the Service is working against the wildlife wing.

For the past several years, California Waterfowl has asked the Secretary of the Interior to resolve the conflicts within his department and ensure the Lower Klamath refuge receives an adequate water supply. In response, the Bureau has released water to the refuge in recent years, and last year, the Bureau requested that refuge management be consulted for the first time on the development of “biological opinions,” which determine water delivery requirement for the endangered fish species for five years at a time.

The refuge provided a schedule of water needs, which fit within the Bureau’s ability to provide. However, lawsuits in the spring of 2018 set aside even more water for the coho salmon and disrupted the schedule. The refuge was required to give back water it had already received, and ended the year with only a trickle of water as the waterfowl migrations arrived and hunting season began.

WHICH BRINGS US TO 2019

New biological opinions, which went into effect on April 2, describe the water supply the Bureau could provide to the Lower Klamath refuge, but they condition that water supply on the refuge and the Klamath Project reaching a shortage sharing agreement. The irrigation districts that have contracted with the Bureau have objected to the idea of this agreement, because it could result in some of their lower priority irrigators being shorted for the benefit of the refuge.

So, under the new biological opinions, the Bureau can only deliver water to the refuge in years where there is so much water that the Bureau can satisfy all the needs of endangered species and the needs of its contractors before it delivers water to the refuge. Those years are few and far between. For all practical purposes, the new biological opinions do not provide any water supply for the refuge in most years. In 2019, despite a water supply that is 130% of average, the farmers themselves are only getting 92% of their contracted supply.

California Waterfowl, together with the Grassland Water District, Ducks Unlimited, Audubon California, Cal- Ore Wetlands & Waterfowl Council, and the Oregon Hunters Association, requested a better analysis of the impacts of the opinions on wildlife, but the Bureau and the fish and wildlife agencies adopted the biological opinions without responding to our request.

Despite the amount of water they are receiving, the coho salmon and the suckers are still on a trajectory toward extinction. And the effects of the Endangered Species Act have created conflict between the various water users, prompting some to use the courts to protect their interests, which has only made things worse.

SO HOW DO WE GET OUT OF THIS MESS?

California Waterfowl is working with all the interests in the Klamath Basin to resolve this incredibly difficult issue— native tribes, irrigators, refuges and counties. Only by working together can the various water users address water quality, timing and shortage issues. Separately, the water users can only impede solutions for each other.

The Secretary of the Interior is on the right track. He designated a special assistant to negotiate a comprehensive agreement within the Klamath Basin that will ensure all water users an adequate water supply for their needs. Such an agreement has been reached before—the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement—but it expired in 2015 because Congress did not ratify it.

Ultimately, California Waterfowl believes in an ecosystem-wide approach in which the refuge serves as a storage and water quality improvement facility that can provide clean water downstream for the benefit of endangered fish. Of course, the refuge would still be managed to meet the habitat priorities of waterfowl, including spring staging habitat, summer brood and molting habitat, and fall staging habitat. This will free up water in the Upper Basin for farmers, while meeting the refuge’s legal obligations to provide habitat for waterfowl. The result will be a win-win solution that benefits all water users in the system.

There are precedents. In the Sacramento Valley, water districts and rice farmers are exploring new ways of managing water that provide benefits to endangered fish, farmers, waterfowl and other birds, and flood control.

The irrigation districts within the Klamath Project have also expressed interest in helping the refuge get a water supply. Even though they are losing water themselves, they are working with California Waterfowl and refuge management to identify ways that water can be made available to the Lower Klamath refuge.

Providing a water supply to the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge is a major priority for California Waterfowl. Our board of directors has convened a task force that is developing a strategy to achieve that result.